It’s a question all impact investors are grappling with: how to quantify the impact of their investments. The Netherlands’ largest pension asset manager APG says it has the answer.

In short

- The SDI Asset Owner Platform maps the contribution of around 8,000 listed companies to the UN Sustainable Development Goals using artificial intelligence.

- APG and its three founding partners drew up a list of 151 product categories, ranging from wind turbines to fire protection solutions, that they believe contribute to the SDGs.

- So far 1,800 of these firms have been identified as contributing to one or more of the 17 SDGs.

APG launched its new SDI Asset Owner Platform, together with its three founding partners PGGM, AustralianSuper and British Columbia Investment Management, in September of last year.

The purpose of the new platform is to map the contribution of around 8,000 listed companies to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) using artificial intelligence. So far 1,800 of these firms have been identified as contributing to one or more of the 17 SDGs.

A Sustainable Development Investment (SDI) is a company that according to the platform’s methodology contributes positively to the SDGs through its products and services.

APG hopes the SDI platform, the first of its kind in the world, will reach “a critical mass of investors who together define the meaning of investing in SDGs,” Claudia Kruse, managing director global responsible investment at APG, told Impact Investor.

The goal of the initiative is to develop a single methodology to measure the contribution of the products and services sold by listed companies to the SDGs.

To this end, APG and its three founding partners drew up a list of 151 product categories, ranging from wind turbines to fire protection solutions, that they believe contribute to the SDGs.

Artificial intelligence

Data analytics firm Entis, which is majority-owned by APG since 2018, developed a model to determine the specific contribution of each company to the SDGs.

“With the help of artificial intelligence tools such as natural language processing, we analyse public documents such as annual reports to identify how much revenue these firms generate by selling products and services that have been classified as SDI-positive,” explains Machiel Westerdijk, co-founder of Entis.

As a result of this analysis, a score between 0-100% is assigned to firms to show the extent to which they are seen as contributing to the SDGs.

Westerdijk admits not all firms are sufficiently granular in their reporting to get a reliable picture of their contribution. “Though most companies are quite specific in reporting their revenues from specific products, some are indeed vague.”

“Therefore we use a confidence measure between one and five stars, which tells you how reliable an assessment is,” he says, adding it is up to the end-investors to determine whether they consider firms with a lower SDI confidence score as impact investments.

Kruse says APG pays “extra attention” to such investments, where the data cannot be immediately extracted from the financial reports. She adds: “Once we have validated SDIs with low initial confidence levels, these also count towards our SDI exposure.”

Kruse could not say, however, what the minimum confidence level of investment is in order for it to count as a sustainable development investment or SDI.

Impact washing

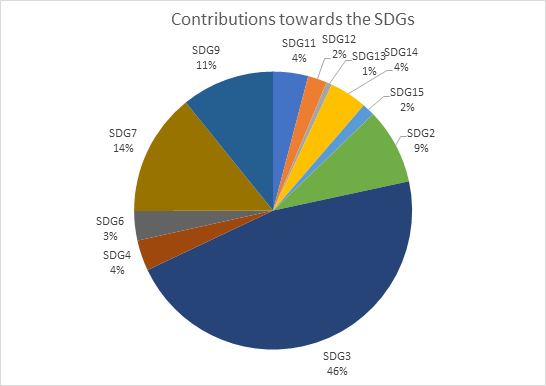

Obviously, the SDGs were not developed as a tool for investors. As a consequence, some SDGs are more investable than others. According to Westerdijk, almost half of the impact (46%) of global listed companies is on SDG 3: Global Health & Well-Being.

SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) and SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) account for most of the additional contributions (see chart).

Westerdijk indicated it is not yet possible to quantify the total contribution to the SDGs of the 1,800 firms that were identified as SDIs. However, the real-world contribution of firms to the SDGs is probably lower than indicated by the model.

For example, sanitary products for Western consumers are regarded as contributing to SDG 3. The real-world impact of such investments could be questioned, as most Western consumers already have affordable access to such products anyway.

Firms that derive a larger proportion of their revenues from developing countries could therefore be considered as having a higher impact than those that are mainly active in developed markets.

APG says it considers the “geographical context” in some industries, such as telecommunication. “Here we factor in geographical capital expenditures and ruralness as we attempt to assess what share of revenues companies get from unconnected rural areas,” says Terhi Halme, senior sustainability specialist at APG. This way, the issue of ‘impact washing’ could be avoided.

“In general, companies often fail to provide sufficient disclosure on regional sales,” says Westerdijk. This makes it difficult to determine how much impact investments really have.

PGB joins platform

The four pension investors are still looking for “a maximum of three” additional asset owners to join the platform and own the underlying methodology, according to Kruse. “However, if we stay with the four of us, that would be fine too,” she says.

Investors can also join the SDI platform as ‘ordinary’ members without providing input to the methodology. The first investor to announce it has joined the platform in this capacity is PGB, a Dutch multi-sector pension fund.

By joining the fund hopes to end “internal discussions” about the meaning of impact and how to measure it, PGB’s policy officer for sustainable investing Yvonne Janssen told our sister publication Pensioen Pro last month.

According to Westerdijk, many investors have shown interest in his methodology. “They often ask us to map the SDG contributions of a specific company for them to compare our results with their own. These are almost always very similar to our results. To us, this shows we are doing something right,” concludes Westerdijk.