The authors of this thought-provoking book advocate the importance of corporate conscience and call for a move away from corporate values to action-oriented corporate principles, writes Christopher Walker.

In brief

- This book has insights that are fascinating – juggling concepts and practical solutions.

- They advocate the importance of a corporate conscience and frighten us with instances of when it has gone missing.

- Among the many thought provoking solutions is a suggested move away from corporate values to corporate principles that are action oriented

Academics who are also business consultants have an interesting perspective. An intellectual overview of problems, and hands-on experience of possible solutions.

This is certainly the case here. Nicholas Ind is a professor at Kristiania University College, Norway, but crucially has also consulted to Adidas, Telia, and Telenor. Oriol Iglesias is an associate professor at ESADE Business School in Spain and has consulted for the likes of Volkswagen, Telefónica, Nestlé, PWC and Banco Santander, among others. Their insights are fascinating – juggling concepts and practical solutions.

They challenge Milton Friedman’s groundbreaking polemic ‘The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits’ (The New York Times, 1970). “While some might advocate that business should not become embroiled in social and political issues, the centrality of business in our world makes this impossible, ” the authors argue.

Comparing revenues to national GDP, they point out Walmart is bigger than Argentina, and Amazon is bigger than Greece. Walmart alone employs some 2.2 million people, while Unilever sources ingredients from more than 1.5 million farmers.

They assert: “Our argument is that environmental and social strategies are only sustainable when they are driven by a strong organisational conscience.”

When conscience goes wrong

It is sometimes easiest to grasp a concept by understanding the exact opposite. And here the authors give us two good examples.

One is the cross-selling scandal at Wells Fargo, where apparently 3.5 million unauthorised consumer accounts were opened, and over 5,000 employees had to be dismissed. What went wrong? They quote Senator Elizabeth Warren’s stinging attack on CEO John Stumpf.

“You know, here’s what really gets me about this, Mr. Stumpf… you squeezed your employees to the breaking point so they would cheat customers and you could drive up the value of your stock and put hundreds of millions of dollars in your own pocket. And when it all blew up, you kept your job, you kept your multimillion dollar bonuses, and you went on television to blame thousands of $12-an-hour employees who were just trying to meet cross-sell quotas that made you rich.”

Otherwise, they cite the Boeing737 Max plane scandal that saw two crashes within five months of launch and the deaths of 346 people. The company “sought to blame pilots rather than accepting its own culpability”. Rather, as one Boeing employee emailed, “this airplane is designed by clowns, who in turn are supervised by monkeys”.

Leadership failure is an important subtext here. In one of several interesting bonus essays, Liz Sweigart of Safe Kids AI, discusses how “our understanding of leadership has evolved over the years” away from the conceptualisation of the ‘Great Man’ to the ‘Moral Integrator’ who “synthesises internal and external stakeholders’ expectations for ethical business conduct with the organisation’s values.”

This ties in well with the authors advocacy of stakeholder co-creation, as seen at Danone which strikes “a reasonable balance among its stakeholders” for action.

Solutions

Indeed, the authors are all for practical solutions and action.

“Corporate values are often expressed through one-word labels such as ‘innovation’, ‘quality’ and ‘honesty’. The problem is that such an approach is highly ambiguous and can be interpreted in any number of ways. Such ambiguity and lack of precision renders corporate values highly subjective.” In place of this they want corporate principles which “must be clearly action-oriented”.

The American retailer Patagonia does this with its first principle, ‘build the best product’. They their “criteria for the best product rests on function, repairability, and, foremost, durability. Among the most direct ways we can limit ecological impacts is with goods that last for generations.”

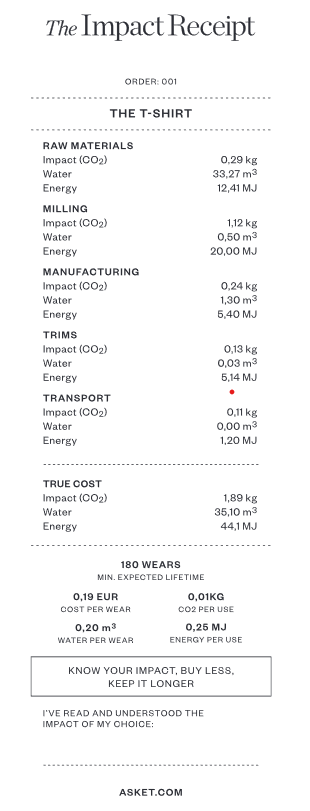

Incidentally, on this point I was fascinated by the ‘Impact Receipt’ (pictured on the right) introduced by the Swedish fashion brand, Asket spelling out the impact in detail.

Otherwise, the authors advocate three key enablers: a collaborative approach to innovation, digitalisation, and ‘servitisation’. The first two will be familiar to impact investors but what is servitisation? “The company that makes the product does not sell it, but instead keeps ownership of it and rents it out.” It thus “has a vested interest in extending a product’s life cycle with a view to maximising rental income.” This contrasts with the old consumerist model.

An example in action is the agreement between Signify (formerly Phillips Lighting) and Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport. Under the accord, the airport pays a fee for the use of the lighting service while Signify retains ownership of the equipment. So “it has a vested interest in ensuring maximum system efficiency, and in recycling equipment once it has reached the end of its life”.