PWC’s climate tech investment report makes for interesting reading. Christopher Walker sits down with the report’s co-author Tarik Moussa to understand the implications for impact investors.

Tarik Moussa CV

- 2014 – present: senior manager, sustainability & innovation

- 2015 – 2017: project manager, Climate and Development Knowledge Network

- 2010 – 2013: Bachelors in Natural Sciences, Cambridge University

Late last year, PWC published its report How can the world reverse the fall in climate tech investment? The need expressed in the title surprised some investors, since there had been much discussion of a coming boom. But as the report observes: “for investors in climate technology ventures, the past two years have been a test of resolve and adaptability.”

The sector is swallowed up by the general crisis in private markets. According to PWC, total venture and private equity investment was down 50.2% year-over-year in 2023.

Private market equity and grant funding in climate tech start-ups specifically has not fallen quite as much – down 40.5% over the same time frame. But the drop still takes climate tech startup funding back to the level of five years ago.

This is obviously a major problem. The PwC research finds that “the world needs to decarbonise seven times as fast as the current rate to limit warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial averages. Technology will play a critical role.” The firm also points out that in the International Energy Agency’s net-zero scenario, over one-third of the emissions reductions occurring in 2050 depend on technologies that are “currently only in development.”

Background to the report and key findings

Tarik Moussa is co-author of the report, and is PWC’s sustainability and innovation leader. He tells Impact Investor that PWC began scrutinising climate tech for good reason. “We saw a step change amongst our clients working in the sustainability status space about four years ago. There was a clear move – from commitment to real action. And this made us determined to carry out an annual report assessing progress.”

Since then PwC have develop three broad strands to their report. Firstly, a comprehensive database of some 8000 climate tech startups with a focus on equity financing. Secondly, discussions each year with key participants to garner their views. And finally a close look at the areas where PWC is seeing real impact, with an attempt to carry out a forward-looking impact analysis.

Investor views

The fall in investment was the most important finding in the latest report. Investors gave two good reasons for the decline in early-stage deals. “We see too many things that are interesting and have a lot of potential, but they are not investable,” says Yair Reem, partner at impact investor Extantia.

Robert Schultz, a partner at Capricorn Investment Group, agrees. “Sometimes we’ll say, ‘this technology is unbelievable, but it’s going to be hard for us to invest in it because they won’t be able to scale it.’”

The second reason mentioned is the reluctance of start-up founders and leaders to raise funds in a weakened market.

“Our assumption is that most companies that can avoid raising external funding now are choosing to do so because they don’t want to take the hit to their valuation,’ says Henry Philipson, a director at venture capital firm Beringea and a founder of industry group ESG VC.

The worry is that the investors who join mid-stage funding rounds will value a company less highly than its valuation from previous rounds, thus diminishing the worth of existing shareholders’ stakes. “So they’ll do internal rounds, bridge-funding rounds, or something else to extend their runway”, he says.

Geographic focus

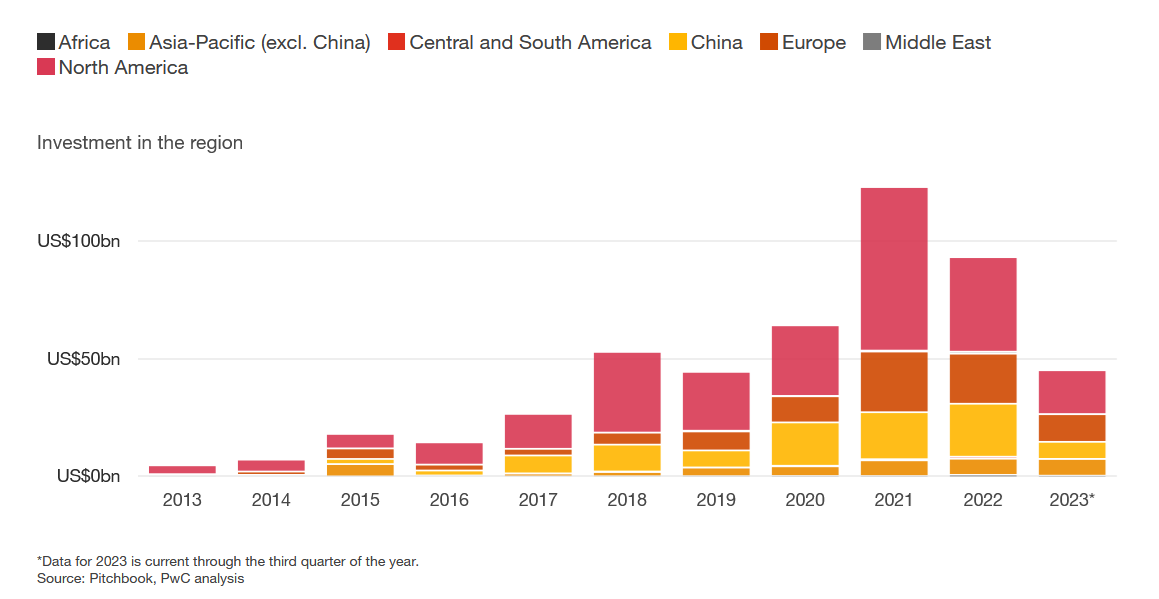

The geographical profile of this decline was interesting. The North American market—largely driven by the US—has long been the focus of climate tech investment. Falling levels of investment in that region accounted for much of the global decline, but there were also significant falls in Europe and China, but not the rest of Asia (see graph).

Reasons to be cheerful

All of this is rather depressing, but there is also some good news to be mined.

“There were two things which were unexpected and pleasing. The extent of the drop, even at 40% or so, was less severe than the fall seen in wider markets. It is pleasing the climate investment has shown more resilience,” Moussa says.

And the second pleasing finding for Moussa, is “the number of new investors emerging.” Certainly, in the report Christian Hernandez Gallardo, co-founder and partner at VC firm 2150 notes, “valuations have definitely come down, so we think it’s a good buyer’s market.”

Schultz agrees, stating: “It’s better for the investment community to find really robust opportunities.”

The report also found one notable positive sector change. Whereas investors directed just under 8% of start-up funding to industrials between Q1 2013 and Q3 2022, they invested 14% in the sector between Q4 2022 and Q3 2023. This sector accounts for more emissions than any other sector of the economy (34%), according to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) figures. Some industrial sub-sectors, such as cement and steel, present especially tough abatement challenges, so this is very good news. It represents a switch away from an over focus on mobility.

“I think we are seeing investors responding to changing policy and regulation,” Moussa says. “In 2021 there was a lot of capital, perhaps in a somewhat indiscriminate manner, targeting the electric vehicles story and issues around that story. We are now seeing broader interest particularly in the industrials area as we have seen significant efforts to encourage this by both the European Union and the US government.”

But Moussa has a warning for investors. “If you go back a few years there was considerable capital waiting to be deployed and investors weren’t particularly looking for strong reasons to deploy it. I think the question is now whether there is a different perception of technology risk. Investors are starting to ask themselves whether technologies will survive in the absence of supportive policy and regulation. I think for some technologies that path is not as clear as was perhaps thought. Classical venture capital investors are averse to taking technology risk, but with some of the climate tech solutions this is inevitable.”

Moussa believes the crucial question is how to attract other kinds of capital in the future. Maybe debt financing, where “investors have different return expectations compared to equity financing may be a way for investors to have a work around on the technology risks,” he adds.