A report from UBS Asset Management and Planet Tracker aims to provide investors in solar, wind and bioenergy with a roadmap on holistic approaches to nature-related risks.

Fossil fuels may have a bigger impact on the environment, but developing clean energy sources such as solar and wind power also comes at a cost to nature that should not be overlooked by investors. That’s the core message from a report just published by UBS Asset Management and non-profit Planet Tracker.

Investors need to consider the opportunity costs and trade-offs between energy transition benefits and negative impacts on nature from clean energy sources, the report’s authors say. While integrating natural capital considerations into investment decisions is complex and only possible with support from decision makers at all stages of planning, financing and implementation, ignoring it could create investment risk, they warn.

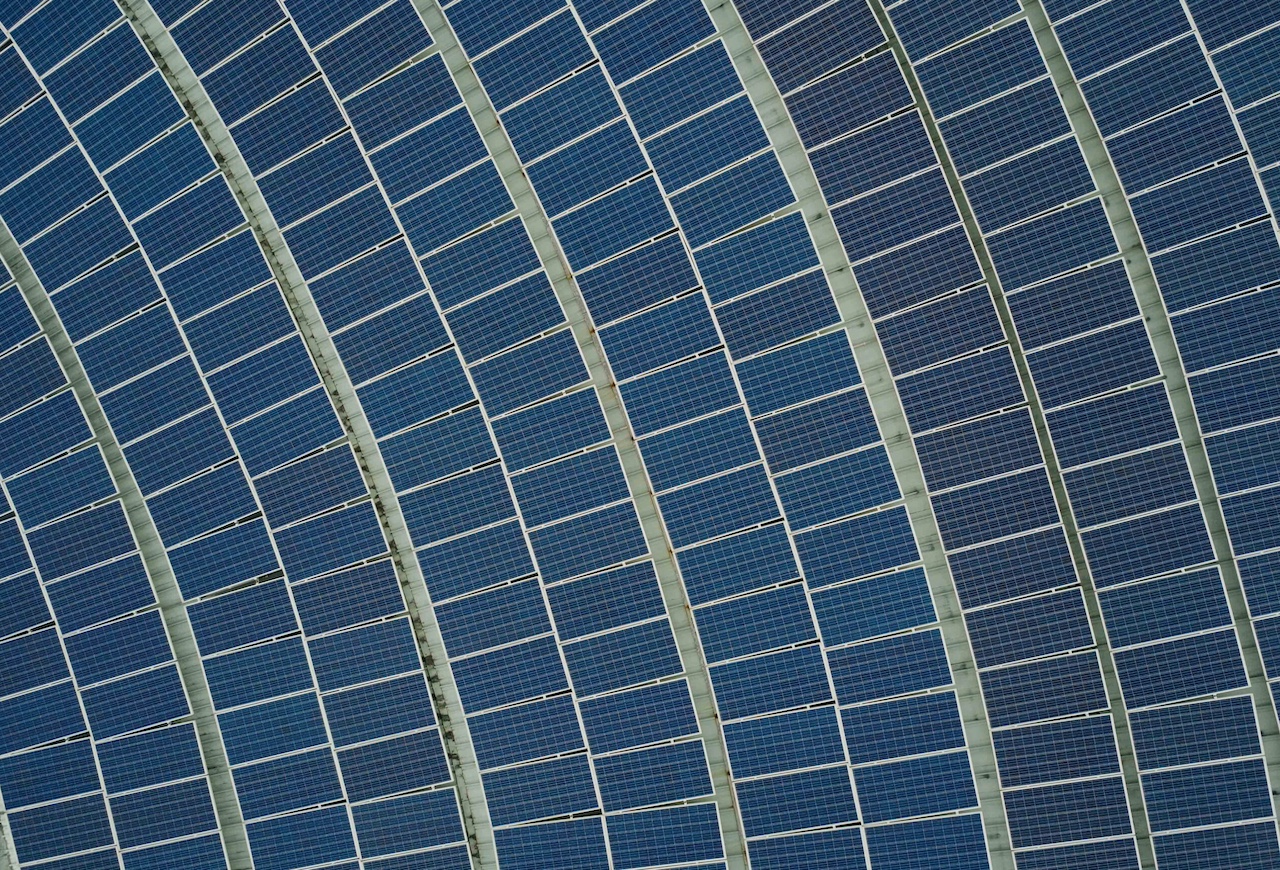

The report, titled ‘Climate meets nature’, aims to provide a practical guide for the investment industry, laying out strategies to minimise the impact on nature arising from the development of solar, wind and bioenergy across the value chain. It looks at three main impacts on nature: land use and site management; habitat loss and damage from the extraction and use of raw materials; and managing the input and output of waste.

These issues are becoming concerns for a growing number of investors, as money floods into clean energy around the world. An International Energy Agency report published earlier this month estimated that some $2trn of the $3trn of global energy investment in 2024 would be channelled to clean energy, much of it going to the solar sector.

Lucy Thomas, head of sustainable investing at UBS Asset Management, told a media roundtable to launch the report that “the transition journey has gotten very, very real” for investors and that such a rapid transformation of the energy sector presented challenges and trade-offs.

“It feels like the time to face into those, and time to get smarter on what the solutions could be to manage some of those complexities,” she said.

The report encourages investors to think about nature impacts of clean energy development in a similar way to that in which they are already being asked to assess climate impacts, taking into account both upstream and downstream impacts of their investments.

That means the nature risks of a solar farm for investors should not only be seen in terms of the impact it is having on the land on which it is being built, according to John Willis, head of research, at Planet Tracker and co-author of the report.

“I’m not saying that isn’t important, but in terms of nature, the solar farm is a tiny part of it, practically all the impact is that upstream, probably about 70%. Think of the mines that you need to develop the solar panels, or the transport to get the solar panels there,” he told the roundtable. “We’re saying just look elsewhere. It’s a sort of warning shot – don’t get caught.”

The report also shines a spotlight on the other end of the clean energy pipeline and the risks involved with handling infrastructure at the end of its life – something the fossil fuel industry already knows does not come cheap. While decommissioning an offshore oil platform may present different issues to taking apart, for example, a wind turbine, the latter still presents challenges.

The report estimates some 14,000 wind turbine blades are due to reach end of life by 2027, all of which will have to be recycled or disposed of safely. Similar end-of-life challenges also face the solar photovoltaic energy sector, which requires 2.5m solar panels to produce 1 gigawatt of power, according to the report.

Expanding reference points

Nature-related risks have been rising up the agenda since the COP15 biodiversity summit in December 2022 produced an agreement intended to boost investment flows into nature protection. That helped kickstart the work of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), whose recommendations aim to provide a framework for company reporting on nature impacts, similar to that provided by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) in the climate sphere. More than 300 companies have so far said will adhere to the TNFD framework.

Willis said the TNFD’s work meant there was already a substantial body of data and information that investors could call on relating to nature-based impacts. That, along with an overlap with climate-related impacts in some areas, meant they did not necessarily need to start from scratch when building nature-related risks into their strategies.

The risks and benefits of deforestation or afforestation was one example of a nature-related risk, which had already been assessed by many investors within climate change strategies due to the carbon impacts.

“You don’t need to start at square one again. Probably, people are further along the line than they actually recognise because of that intersection,” Willis said.